Update (2013-08-31): Apple has asked me to refrain from publishing any details on this security-relevant bug for the time being; I hope that a fix will be released soon. When that happens (or after a reasonable amount of time has passed), the original post will be restored.

Until then, I would strongly advise against using Mobile Safari when any X.509 client certificates are stored on an iOS device, e.g. an S/MIME encryption/signing certificate. Other in iOS, like Chrome, are not affected; neither are browsers on OS X (including Safari).

Second update (2013-10-23): Since my original post, iOS 7 has been released; the bug described below seems to have been fixed. The issue is of course still present in iOS <= 6.1.4. Since it seems to be Apple's policy not to release security fixes for discontinued OS versions, this leaves older devices like the original iPad and the iPod touch (up to the 4th generation) vulnerable. That's unfortunate, but since I'm definitely not the only one who knows about the issue, here is my original post. Be sure to take care when using any client certificates on an older iOS device.

tl;dr: If you have an S/MIME or other X.509 client certificate installed on your iOS device, Mobile Safari will hand it out to any web server that asks for it – without asking you.

Recently, I've looked into TLS with client certificates, specifically into how the various browsers and operating systems implement them.

In addition to authenticating a server and securing a connection between this server and an anonymous client, TLS also allows the client to identify itself to the server using its own X.509 certificate. This mode is only used by very few services using TLS, which could be attributed to the difficulty of issuing client certificates in the first place, and protecting them against both theft and loss later on.

However, I think that there are more issues with client certificates than that.

First of all, the client certificate is transmitted to the server unencrypted, which means that everybody between the client and the server is able to identify the user trying to connect. Since an X.509 certificate frequently contains personal information like the user's full name and mail address,this seems like a bad thing to do.

Additionally, TLS client certificates are used in a way that doesn't provide deniable authentication. To prove that the client is in posession of the private key corresponding to the X.509 certificate, he signs all previous handshake messages. Among other things, this contains a (client-provided) timestamp and the server certificate; the signature of those values can be used to prove that that somebody with access to the private key initiated a connection to a specific server at a specific time. Even worse, this signature is also still transmitted in plaintext (symmetric encryption and authentication aren't used before the next message (Finished) in the handshake.

Considering those (in my opinion substantial) disadvatages of the implementation of client certificate authentication in the current version of TLS, it might be better to perform authentication inside the secure TLS channel at the application layer, which is exactly how it's done for the vast majority of web services (via HTTP cookies) and other protocols protected by TLS.

(An even better solution would be a TLS extension that moves the client authentication inside the secure channel, or even uses something analogous to the server authentication in TLS, which might be able to provide deniable authentication for the client as well. But the rate at which TLS extensions and updates are adopted by software vendors is not exactly instantaneous.)

Since the status quo seems to be exactly that (whether that's due to the difficulty of issuing certificates or to the mentioned disadvantages of them with TLS), is there anything left to worry about?

There is: Broken browsers.

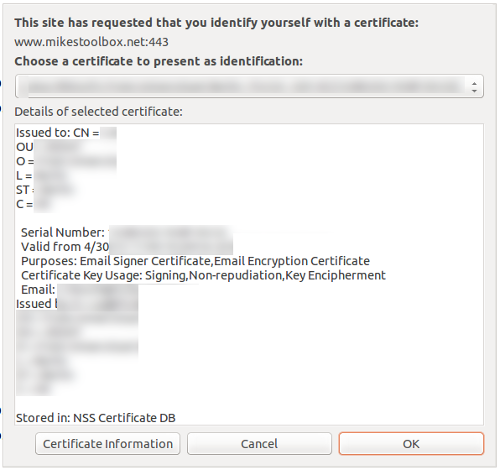

Probably due to their minimal use in real-word applications, some browsers' TLS client certificate implementations are a bit sloppy. When an HTTP server requests a client certificate (using the Certificate Request message in the TLS handshake), most of them display a pretty technical-looking dialog to the user, who might or might not understand what's going on.

This is clearly not an example of good user experience. So let's check how Apple does it in iOS...

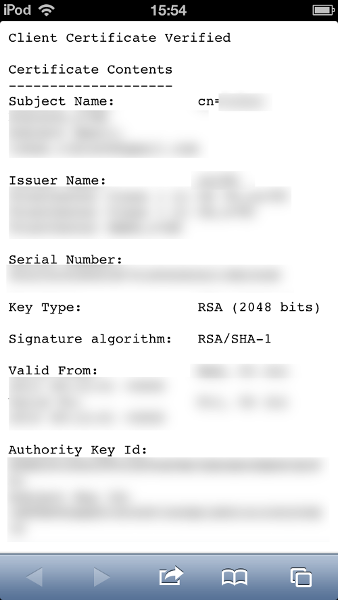

Oops. They don't. They just pick the first certificate available (in my case, this is an S/MIME certificate that includes my full name, my employer and my e-mail address), transmit it and authenticate to the server by non-repudiably signing the TLS handshake – all in plaintext. All the previously mentioned caveats apply, only that the user has no choice about the matter in the first place.

If you want to try it yourself, just visit Mike's Toolbox with Mobile Safari, accept the self-signed server certificate and look for your name or e-mail address on that page.

This problem has been mentioned before publicly at least once, more than one year and one major OS version ago. On the desktop, this has already been fixed (with OS X 10.5.3); I'm really hoping it will be fixed with iOS 7 as well.

There are comments.